In Their Image

Posted on May 30, 2012

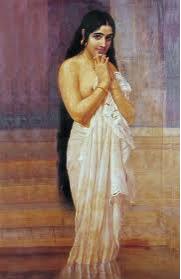

In her book, Freedom and Destiny: Gender, Family and Popular Culture in India (Oxford University Press, 2009), Patricia Uberoi brings a gender perspective to bear on the representation of the family in India, incorporating childhood, courtship, marriage and sexuality into an analysis of three different aspects of popular culture: calendar art, commercial Hindi cinema and romance fiction in magazines. She also offers some reflections on the wider contradictions and dynamics of Indian modernity and the concept of nation-building.Calendar art is contrasted with the ‘fine’ art of the art gallery. It is a generic name for a style of popular, mass-produced prints in colour or black and white, although calendars can take up a variety of other forms. Uberoi argues that images of women and babies in calendar art objectify women, turning the female body into a commodity. These commoditized forms are conspicuous not only in this medium but also in other related media such as advertisements and film hoardings. Uberoi describes how, time and again, women become ‘othered’ and ‘controlled’, when being exhibited before a male gaze as objects of desire. This is emphasized by the association of images of women with a range of consumer products—a panoply of market goods. Further, Uberoi explains how this calendar art can also be characterized by a metonymical juxtaposing of sacred and secular imagery. A series of striking images serves to illustrate this.

Other common motifs of these media include cute pets, flowers and idyllic landscapes. Babies are particularly popular, she argues, and certain artists or studios are known to specialize in baby pictures, just as others specialize in women deities, film stars and other ‘beauties’ or scenery. She associates these calendar art images with symbols of nation-building, national modernity and social progress in the way that they evoke the idea of ‘Mother India’ as the protector of the land and its people and as the vanquisher of enemies. The work of late nineteenth-century salon painters are also of note in this regard, in particular Raja Ravi Varma (1842–1906), who is widely credited with establishing the representational style and pioneering the mass production of colour prints in India.

Many of the calendars that feature babies itemize the children into familiar adult roles, which in turn contribute towards building the image of a progressive, prosperous and secure nation. Furthermore, children are portrayed both as objects of desire and consumers in their own right. Calendar art thus rests on a plane of tension between ‘unity’ and ‘variety’, between tradition and modernity, while the images of women and children are specifically connected with that of the middle classes in India.

Turning her attention to commercial Hindi cinema, Uberoi describes how the images of the ‘perfect’ Indian family, its cultures, values and traditions seek to preserve a feeling of Indianness in the hearts of the Indian diaspora. She illustrates her point by referring to hit Bollywood films such as, Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge and Pardes. Hindi cinema, as it is commonly recognized, compartmentalizes the conflicting dimensions of wifehood—procreativity and sexuality, love as duty and love as sexual passion—into distinct social spaces. Ultimately the woman is seen to maintain the traditional Indian values, ready to make a sacrifice for them wherever and whenever she is required to.

Namaste London (2007) is a more contemporary example than those provided by Uberoi, in the way that it endorses the Indian family values that are fast disappearing in the contemporary world. Shot in London and Punjab, the film focuses on a father’s wish for his daughter to learn the ways of western culture and lifestyle. Jazz, played by Katrina Kaif, has been born and brought up in London and thinks partying and drinking in pubs is all that there is to life. She also thinks that as an adult she has a right to do what she feels like, which shocks her dad. This is the generation gap that the director seeks to illustrate—the young are set free to follow their will in another country while the parents pine for a good Indian boy for their daughters, having initially encouraged their children to learn the ways of the West.

The challenge of being and remaining Indian in a globalized world is one that must be met equally by those at home and abroad. With reference to Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson, she describes how the images of the family in Bollywood films depict the sort of generic image, a utopia, with which anyone could associate. It therefore stands to reason that, whether at home or abroad, it is the family system that is recognized as the social institution which quintessentially defines being Indian. These films operate as a site from where the perceived problems in the Indian middle class diaspora are addressed. The traditional patriarchal authority and inter-family alliances of marriage are ultimately reaffirmed.

Uberoi finally addresses the subjects of ‘post-marital romance’ and the ‘tribulations of courtship’ as portrayed in romantic literature in women’s magazines. Stories about romantic relationships after marriage became common in the late 1980s and early 90s. Uberoi highlights the importance of these short stories as they demonstrate to what extent the woman has to adjust in a marriage whenever required. She also observes the significance of a third character that acts as a mediator during conflicts between husband and wife: ‘The protagonist immediately identifies with that person and accepts the advice implicitly or explicitly proffered.’

Compared to the stories of post-marital love, the tales of romantic courtship are less satisfying and analytically more intractable. The former begins with marriage and ends in love, while the latter is the reverse. Love relationships are rarely portrayed as sexual and it is not endorsed that such relationships result in enduring love or marriage. In such cases the only ‘happy solution’ is that the relationship becomes ‘formalized and sacralized in marriage—provided the parents are otherwise well suited to each other.’

As much as all these media threaten the institution of Indian marriage and the Indian family system, via feminist critiques, they also become the ground in which these traditions are compounded. This book is a valuable contribution to its field in the way its author achieves accessibility by avoiding sociological jargon without sacrificing disciplinary rigour or her underlying feminist standpoint. However, by focusing so much on popular culture, Uberoi has limited her argument to a critique of the moral economy of the family. She is much more concerned with disproving or approving the ideal, imagined Indian family than she is with examining the reality. Despite her ability to present popular culture as an effective resource for achieving new sociological insights into contemporary issues and process, Uberoi only shows one side of the coin. The other—hidden—face is where women in modern India are still suffering for being women and struggling for autonomy.

Roshni Sharma

Leave a comment ×