Hide and Seek: Perceived Being and Being Perceived in Beckett’s Film

Posted on May 24, 2012

02. 03. 1936Monsieur,

I write to you on the advice of Mr Jack Isascs, of London, to ask to be considered for admission to the Moscow State School of Cinematography. Born 1906 in Dublin and “educated” there. 1928-30 lecteur d’anglais at Ecole Normale, Paris. Worked with Joyce, collaborated in French translation of part of his “Work in Progress” (NRF, May 1931) and in critical symposium concerning same (Our Examination, etc.) Published “Proust” (essay, Chatto & Windus, London, 1931), “More Pricks Than Kicks” (short stories, do., 1934), “Echo’s Bones” (poems, Europa Press, Paris, 1935). I have no experience of studio work and it is naturally in the scenario and editing end of the subject that I am most interested. It is because I realise that the script is function of its means of realization that I am anxious to make contact with your mastery of these, and beg you to consider me a serious cinéaste worthy of admission to your school. I could stay a year at least.

Vuilliez agréer mes meilleurs hommages.

Samuel Beckett

This is the remarkable letter that never reached its recipient—Sergei Eisenstein—which could have otherwise dramatically changed Samuel Beckett’s creative life (It has been published by Seagull Books in The Eisenstein Collection, edited by Richard Taylor). Evidently, Beckett’s interest in pursuing a career in cinema was serious, as in this letter he claimed he would dedicate at least a year of his life to learning the craft from Eisenstein. As it turned out, Beckett himself would only ever make one contribution to film: the 1965 short, Film. The fact that the occasion of the film’s making provoked Beckett to make his one and only trip to the United States (it is filmed in New York) in order to have an active role in its production is a testament to his enthusiasm for the medium. In contrast, he neglected to travel for any of his theatre productions (as Katherine Waugh & Fergus Daly explain), even the ones made by his favourite director, Alan Schneider, whom Beckett requested to direct this film.

Eisenstein himself had famously remarked upon the influence of nineteenth-century literature on early cinema, in terms of technique, theme and narrative. Later, modern fiction would in turn take formal influence from the matured medium of film. Cinematic effects such as montage, the fragmenting and re-threading of varied viewpoints and narratives, came to be common literary devices that would lead both literature and film to an ongoing mutual exchange of ideas. When questioned on his treatment of literary texts in his own films (in an interview for Indian State TV that has been long since lost) Satyajit Ray commented on his use of film not merely as adaptation or translation, but as critique. This suggests, beyond a mere exchange or pastiche, the possibility of a dialogue between images and text, as two distinct voices with corresponding ideas.

Beckett’s penchant for philosophy is clear in his literary works, which reflect upon certain epistemological concerns portrayed through his characters’ often playful, occasionally oblique, antics. In Film he formulates similar intellectual observations visually. The fact that it is silent (except for the instructive ‘Shhh’ at the beginning) emphasizes vision as the film’s subject and form. Taking his departure for the script from the words of the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher, Berkeley, ‘Esse est percipi‘ (‘to be is to be perceived’), Beckett uses film to address certain problems of perception, mainly how it is unavoidable, for no matter how hard you might escape the perception of others, you can never fully escape your own mind’s eye.

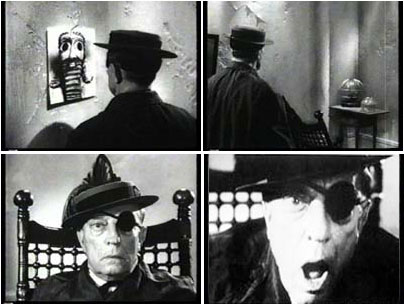

There is a tragicomic element to this state of affairs that is not lost on the film’s screenwriter, nor on its protagonist, ‘O’, played by the silent-cinema phenomenon Buster Keaton. Seen here in his later years, Keaton proves still to be an upholder of the absurd, although the humour, where it is noticeable (Simon Critchley has questioned whether the film is indeed funny at all) is less delightful (compared to The General for example) and more off-beat, unnerving even (an altercation with a puppy and a kitten in a sparse and shabby room is perhaps the exception to this).

The other key protagonist in Film is ‘E’, played by the camera itself. The camera is the ‘Eye’ with which we, the viewers, pursue O, the ‘Object’. Along the way, we encounter passers-by who are also disturbed by the camera’s gaze. O goes to great pains to avoid all exterior perceptions of himself, from animate and inanimate sources, that close in around him, literally walling him in. A segment of the film that features O sifting through an envelope filled with photographs provides a momentary but poignant divergence, as he tenderly handles a selection of images from his past, featuring significant moments and relations, before promptly tearing them to pieces and stamping out the remains. It seems there are some reflections that are harder to part with than others. Not only is perception subjective and discriminative but our rejection of it is too.

Throughout the film both E and O, the invisible perceiver and the elusive perceived, seem engaged in a mutual dance, spinning and gliding about as if in tandem. It is not until O lets down his guard by falling asleep that E gets to play the advantage. Here we are confronted with the irony that the perceiver O has been trying to evade throughout is actually himself. Furthermore, O only has one eye (depth perception is said to be reduced with one eye). The film begins and ends with the image of a blind, blinking eye, confirming that the eye alone is impotent without an object, just as the object is incomplete if it is not being perceived.

Becky Ayre

Leave a comment ×